A review of the pioneering and so far most important book about anti-natalism by the philosopher David Benatar

Undoubtedly the academic thinker who is most associated with anti-natalism is the philosopher David Benatar. In 2006 Benatar published a book called Better Never to Have Been in which he argues that coming into existence is always a serious harm. The entire book is an attempt to explain why he argues so and why everyone who argues differently is wrong.

Benatar’s basic argument is that although the good things in one’s life make it go better than it otherwise would have gone, one could not have been deprived by their absence if one had not existed. Those who never exist cannot be deprived. However, by coming into existence one does suffer quite serious harms that could not have befallen one had one not come into existence.

This argument is kind of a summarized version of the book’s two main arguments:

- Coming into existence is always a serious harm regardless of the quality of one’s life (known as the asymmetry argument), an argument Benatar elaborates in the second chapter of the book.

- People’s quality of life is bad in itself and much worse than most of them tend to think it is, an argument Benatar elaborates in the third chapter of the book.

Alongside these two central arguments, Benatar also addresses many other issues as they relate to reproduction such as pro-natalism, some common issues in population ethics (the non-identity problem, the mere addition problem, the repugnant conclusion, problems with average utilitarianism, etc.), abortion, ableism, extinction, suicide, death and more. However, in order to stay focused on the main thesis of the book, and to keep this review’s length reasonable, we’ll concentrate on the two central arguments alone.

The Asymmetry Argument

Benatar argues that we rarely contemplate the harms that await any newborn child such as pain, disappointment, anxiety, grief, and death. For any given child we cannot predict what form these harms will take or how severe they will be, but we can be sure that at least some of them will occur. None of this happens to anyone who doesn’t exist. Only existers suffer harm.

The optimists, argues Benatar, will claim that this is only part of the story. Not only bad things but also good things happen only to those who exist. Pleasure, joy, and satisfaction can only be had by existers. Many claim that we must weigh up the pleasures of life against the evils, and as long as the former outweigh the latter, the life is worth living.

Benatar replies to this claim using the asymmetry of pleasure and pain.

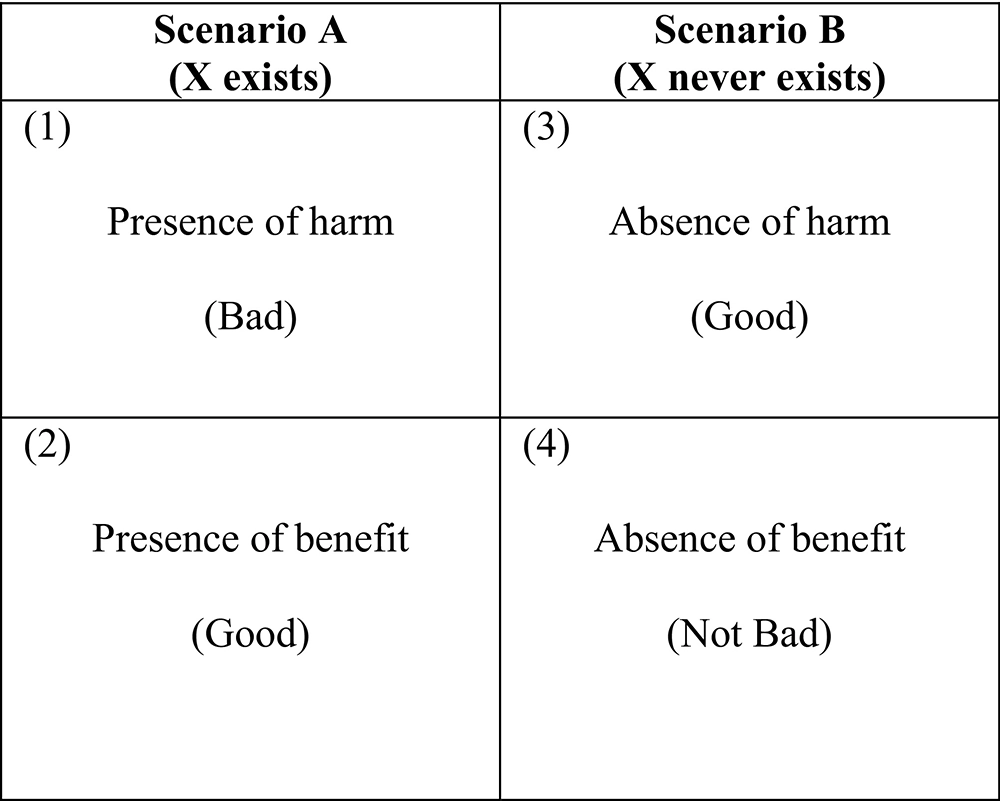

He suggests thinking about pains and pleasures as exemplars of harms and benefits and argues that it is uncontroversial to say that:

(1) the presence of pain is bad,

and that

(2) the presence of pleasure is good.

However, such a symmetrical evaluation does not seem to apply to the absence of pain and pleasure, for it strikes me as true that

(3) the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone, whereas

(4) the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence is a deprivation.

Or in a tabular form:

There is then a crucial difference between harms (such as pain) and benefits (such as pleasures) that derives the conclusion that existence has no advantage, but it has a disadvantage, in relation to non-existence. That is because the absence of pleasures in non-existence is not bad, while the absence of pain in non-existence is good.

(3) has a significant advantage over (1). But (2), although better for X in scenario A, has no advantage over (4) in scenario B. Therefore there is no net benefit in existing over non-existing. Existence has no advantage in terms of pleasures and non-existence has an advantage in terms of preventing harms. In other words, Benatar’s basic idea is that non-existence has an advantage in relation to harm because non-existence without harm has and advantage over existence with harm, but existence has no advantage over non-existence in relation to pleasure because existence with pleasure has no advantage over non-existence without pleasure, therefore existence is always in disadvantage against non-existence, and therefore, as the book’s title implies, it is better never to have been.

Benatar is aware that many would probably wonder how the absence of pain could be good if that good is not enjoyed by anybody. Absent pain, it might be said, cannot be good for anybody, if nobody exists for whom it can be good.

The judgement made in 3 (the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone) is made with reference to the (potential) interests of a person who either does or does not exist. To this it might be objected that because (3) is part of the scenario under which this person never exists, (3) cannot say anything about an existing person. This objection would be mistaken because (3) can say something about a counterfactual case in which a person who does actually exist never did exist. Of the pain of an existing person, (3) says that the absence of this pain would have been good even if this could only have been achieved by the absence of the person who now suffers it. In other words, judged in terms of the interests of a person who now exists, the absence of the pain would have been good even though this person would then not have existed.

Benatar argues that we need to examine what (3) says about absence of pain of one who never exists – of pain, the absence of which is ensured by not making a potential person actual, and (3) says that this absence is good when judged in terms of the interests of the person who would otherwise have existed. We may not know who that person would have been, but we can still say that whoever that person would have been, the avoidance of his or her pains is good when judged in terms of his or her potential interests. If there is any sense in which the absent pain is good for the person who could have existed but does not exist, this is it.

Benatar argues that once we understand that to be created can mean to be harmed, we can speak rather freely about the idea that to never be created can be the better option. And by that we don’t say that it is better for the one who doesn’t exist, or that the one who doesn’t exist has benefited from his non-existence. It is clear to Benatar that even speaking about the ones who have never been is strange, because the ‘non-existers’ is a referenceless term. Obviously there is no such thing as non-existing people. It is simply a convenient term that can be used in a plausible way.

Clearly (3) does not entail the absurd literal claim that there is some actual person for whom the absent pain is good.

Benatar’s point is that the absence of pain is good if someone who doesn’t exist would have existed, and that for someone who does exist it would have been good if that someone didn’t experience pain (even if the only way to prevent this is by that someone never existing).

Benatar doesn’t argue that someone who never has been is literally in a better state (as someone who never has been isn’t and never was in any state), but rather that existence is always a harm to the ones who exist. In other words, although we can’t say about the ones who never have been that non-existence is better for them, we can say that existence is worse in relation to the option of never having been.

People find it hard to accept that coming into existence is always a harm. Most people don’t regret that they were created. Many people are even happy that they were created because they feel that they are enjoying their lives. But these assessments are mistaken, argues Benatar. The fact that someone enjoys their life doesn’t make their existence better than the state in which they never have been, since had that person never been no one would have been deprived of the pleasures that person had experienced in their existence, and therefore the absence of this good is not bad. On the other hand, it makes total sense to regret the existence of the ones who feel that they are not enjoying their lives. In a case like this, had someone never existed there would be no one to suffer this life. And that is good, despite that there would be no one who would benefit from that good.

It could be argued that the same way preventing pain is good, preventing pleasure is bad.

Benatar argues that this claim is wrong, evidently we don’t lament the ones who were never created because they miss pleasures, but we do lament the ones who were created and are miserable.

For a similar reason Benatar opposes the option of writing about the absence of pain that it is not good and about the absence of pleasure that it is not bad. The reason is that according to him saying that the absence of pain is ‘not bad’ is too weak. Preventing pain is not ‘not bad’ but good.

In support of the asymmetry argument, and to convince others of its validity, Benatar suggests it as the best explanation for at least four other asymmetries that are quite plausible.

First, the asymmetry between (3) and (4) is the best explanation for the view that while there is a duty to avoid bringing suffering people into existence, there is no duty to bring happy people into being. In other words, the reason why we think that there is a duty not to bring suffering people into existence is that the presence of this suffering would be bad (for the sufferers) and the absence of the suffering is good (even though there is nobody to enjoy the absence of suffering). In contrast to this, we think that there is no duty to bring happy people into existence because while their pleasure would be good for them, its absence would not be bad for them (given that there would be nobody who would be deprived of it).

The second quite plausible asymmetry that Benatar’s asymmetry best explains (and therefore supports Benatar’s asymmetry) is that whereas it is strange (if not incoherent) to give as a reason for having a child that the child will thereby be benefited, it is not strange to cite a potential child’s interests as a basis for avoiding bringing a child into existence. If having children were done for the purpose of thereby benefiting those children, then there would be greater moral reason for at least many people to have more children. In contrast to this, our concern for the welfare of potential children who would suffer is a sound basis for deciding not to have the child. If absent pleasures were bad irrespective of whether they were bad for anybody, then having children for their own sakes would not be odd. And if it were not the case that absent pains are good even where they are not good for anybody, then we could not say that it would be good to avoid bringing suffering children into existence.

Moreover, if the absence of pleasure was bad regardless of whether it is bad for someone, then people would have a moral incentive to create as many people as they can, but it is agreed that there is no such moral incentive. Although some people consider it a blessing and even a religious virtue, very few consider it a moral obligation, all the more so to create as many as possible.

As a third support for his asymmetry argument Benatar suggests the retrospective judgements asymmetry. Bringing people into existence as well as failing to bring people into existence can be regretted. However, only bringing people into existence can be regretted for the sake of the person whose existence was contingent on our decision. This is not because those who are not brought into existence are indeterminate. Instead it is because they never exist. We can regret, for the sake of an indeterminate but existent person that a benefit was not bestowed on him or her, but we cannot regret, for the sake of somebody who never exists and thus cannot thereby be deprived, a good that this never-existent person never experiences.

One might grieve about not having had children, but not because the children that one could have had have been deprived of existence. Remorse about not having children is remorse for ourselves—sorrow about having missed childbearing and childrearing experiences. However, we do regret having brought into existence a child with an unhappy life, and we regret it for the child’s sake, even if also for our own sakes. The reason why we do not lament our failure to bring somebody into existence is because absent pleasures are not bad.

For the fourth and last support for his asymmetry argument Benatar suggests the asymmetrical judgements of distant suffering and uninhabited portions of the earth or the universe. Whereas, at least when we think of them, we rightly are sad for inhabitants of a foreign land whose lives are characterized by suffering, when we hear that some island is unpopulated, we are not similarly sad for the happy people who, had they existed, would have populated this island. Similarly, nobody really mourns for those who do not exist on Mars, feeling sorry for potential such beings that they cannot enjoy life.

Yet, if we knew that there were sentient life on Mars but that Martians were suffering, we would regret this for them. We regret suffering but not the absent pleasures of those who could have existed.

The argument that coming into existence is always a harm can be summarized as follows: Both good and bad things happen only to those who exist. However, there is a crucial asymmetry between the good and the bad things. The absence of bad things, such as pain, is good even if there is nobody to enjoy that good, whereas the absence of good things, such as pleasure, is bad only if there is somebody who is deprived of these good things. The implication of this is that the avoidance of the bad by never existing is a real advantage over existence, whereas the loss of certain goods by not existing is not a real disadvantage over never existing.

Therefore, even in the absolutely hypothetical state of a person who enjoys each and every moment of their life except for one moment and so the summation of this person’s life would have been great according to that person, Benatar would still argue that it is better for that person as well never to have been because had that person never come into existence they wouldn’t experience that one unpleasant moment and they wouldn’t be deprived of any of the pleasurable moments. That person wouldn’t be harmed by not experiencing the pleasures had that person never existed, and they are harmed by the one bad experience they endure if they do exist, therefore it is always better never to have been. No matter how good it can be, not to exist can’t harm the one who never existed because the ones who never have been aren’t existing in some kind of other dimension observing all the pleasures being taken away from them, or feeling deprived of them in any way. But their suffering will necessarily exist if they would exist.

How Bad Is Coming into Existence?

The conclusion of Benatar’s asymmetry argument is that as long as life contains even the smallest quantity of bad, coming into existence is a harm. However, Benatar realizes that this argument is way too radical for most people, and anyway, although it is derived from his asymmetry argument, it doesn’t reflect real life. In the real world, even among the luckiest people in the world, life contains much more than the smallest quantity of bad. Accordingly, he argues that whether or not one accepts his conclusion, one can recognize that a life containing a significant amount of bad is a harm. Therefore Benatar devotes the third chapter of his book to the claim that people’s lives contain much more bad than is ordinarily recognized. He hopes that if people realized just how bad their lives were, they might grant that their coming into existence was a harm even if they deny that coming into existence would have been a harm had their lives contained but the smallest amount of bad.

Thus his third chapter can be seen as providing a basis, independent of asymmetry and its implications, for regretting one’s existence and for taking all actual cases of coming into existence to be harmful.

Benatar is aware that most people think that their lives are fine all in all. And he is aware that many are asking how life can be so bad if most of those who are living it deny that it is bad? Or how coming into existence could be a harm if most of the created people are glad they were created? his answer is doubting the credibility of these self-evaluations.

There are a number of well-known features of human psychology that can account for the favorable assessment people usually make of their own life’s quality. It is these psychological phenomena rather than the actual quality of a life that explain this wrong positive assessment.

The first psychological phenomenon Benatar mentions is the Pollyanna Principle, or the tendency towards optimism. This phenomenon has all kinds of expressions, for example, people’s inclination to recall positive rather than negative experiences. This selective recall distorts our judgement of how well our lives have gone so far.

And it is not only assessments of our past that are biased, but also our projections or expectations about the future. We tend to have an exaggerated view of how good things will be.

Many studies have consistently shown that self-assessments of well-being are markedly skewed towards the positive end of the spectrum. For instance, very few people describe themselves as ‘not too happy’. Instead, the overwhelming majority claims to be either ‘pretty happy’ or ‘very happy’. Contrary to any statistical logic, almost all people insist that they are better off than most others or than the average person, in almost every aspect, including quality of life and their happiness level.

There is inconsistency between relevant objective factors such a people’s health and their subjective assessments of well-being. Meaning, people report being happy even when their objective condition is bad, and that is at least suspicious. Even people who did express dissatisfaction with their health situation, were in the positive end of the spectrum of the reports. Within any given country, the poor are nearly as happy as the rich are. Nor do education and occupation make much difference. Meaning, factors that it is very reasonable to assume have a major effect, practically have a very small one and that indicates a structured problem with self-assessments.

Another well-known psychological phenomenon that Benatar mentions as distorting people’s ability to make a reliable self-assessment of well-being is the phenomenon of what might be called adaptation, accommodation, or habituation. When a person’s objective well-being takes a turn for the worse, there is, at first, a significant subjective dissatisfaction. However, there is a tendency then to adapt to the new situation and to adjust one’s expectations accordingly. Meaning, even if the objective situation is bad or at least worse than it used to be, subjectively, it is not viewed as bad as it actually is because people’s subjective sense of well-being tracks recent change in the level of well-being better than it tracks a person’s actual level of well-being.

Another important psychological phenomenon for that matter is comparison with the well-being of others. It is not so much how well one’s life goes as how well it goes in comparison with others that determines one’s judgement about how well one’s life is going. If compared with the lives of others my life is fine then I think that my life is fine despite the fact that it might be very bad in itself. In other words, if people’s lives are hard, painful, tiring, pointless, and frustrating, but as far as they are concerned less than the lives of others around them, then they assess their lives as better than they really are.

Obviously even if it is true that someone’s life is better than the life of everyone around, it can still be awful.

There is an evolutionary logic behind these mechanisms and that is biological preservation. They assist the promotion of reproduction and the prevention of suicides. Actually there is a biological bias against pessimism because pessimists are more inclined to end their lives and less to reproduce, and so, generally speaking, natural pessimism, is less likely to be spread.

Benatar further argues in that context that people tend to ignore just how much of life is characterized by negative mental states. And he is not necessarily referring to dramatic things, but rather to daily negative experiences, such as hunger, thirst, bowel and bladder distension, tiredness, stress, thermal discomfort (that is, feeling either too hot or too cold), and itchiness. For billions of people, at least some of these discomforts are chronic. These people cannot relieve their hunger, escape the cold, or avoid the stress. However, even those who can find some relief do not do so immediately or perfectly, and thus experience them to some extent every day. In fact, if we think about it, significant periods of each day are marked by some or other of these states. Only because this is everyone’s reality, and everyone is so used to it, and from such a young age, the fact that everyone’s life is so constantly accompanied by so many negative mental states goes under the radar.

And to all these daily negative mental states, we need to add less routine yet quite common negative mental states such as pain, frustration, sickness, allergies, anger, nausea, sadness, body image issues, boredom, shame, guilt, loneliness, grief, etc.

Benatar argues that as opposed to what most people think, there is much more frustration than satisfaction. Meaning there are many more unfulfilled needs and desires than there are fulfilled ones.

Most of the satisfaction is due to fulfilling desires. If there are no desires there is no need to fulfill them. Had all the desires been immediately and fully satisfied, things would have been better but no desires are ever satisfied immediately and perfectly, and many never are. Most people are dissatisfied most of the time, claims Benatar. Every satisfaction is preceded by a desire and an unfulfilled desire is a negative experience. Every satisfaction of a desire starts with frustration until it is fulfilled. Theoretically satisfaction can come quickly, but it doesn’t. and when it comes, usually it is temporary. And not only do we not get what we want, we suffer from the fear of losing what we do get.

Benatar mentions Schopenhauer who argued that life is a constant state of striving or willing, meaning a constant state of dissatisfaction, since attaining that for which one strives brings a transient satisfaction, which soon yields to some new desire.

But Benatar claims that one need not go as far as Schopenhauer since it is sufficient to realize that we must constantly make efforts to satiate needs and desires, while these come easily and naturally. We must work our entire lives so as to have a roof above our head to protect us from heat and cold, and to have food on our table, but negative mental states such as hunger, thirst, cold or heat come naturally and effortlessly. We need to work so as not to suffer but suffering comes naturally and easily. We must do things in order to have positive experiences, these don’t come naturally and easily. Suffering does. And that is a strong testimony against the claim that life is good in itself.

So according to Benatar people’s quality of life is much worse than they tend to think it is, and it is their psychology that enables them to think that their lives are much better than they actually are. Using a more accurate view of people’s quality of life, we’ll be in a much better starting point to judge whether to create a new person is morally wrong considering that starting someone’s life is an action that by definition can’t be to benefit that person. And as far as Benatar is concerned, considering that life is full of harms, the way human life is characterized, it is certainly morally wrong.

These psychological mechanisms cause people to think that they and their children are immune to all life’s harms. And there are maybe a few who don’t experience all these harms, but these are a lucky nonrepresentative tiny minority.

Only a handful are spared from experiencing significant suffering, and everyone with no exception will experience at least some of his list of harms. Benatar argues that even if there are cases that these harms are spared, and that the life of these people are better than he claims they are, these cases are extremely rare. They are so rare that for each of these cases there are countless cases of bad lives.

There are people who know that their child will be one of the unlucky ones, but no one knows that their child will be one of the lucky ones. Therefore Benatar likens reproduction to Russian Roulette as great suffering may be caused to every created person. Even the most privileged people can create a person who will suffer greatly if for example that person is raped, brutally attacked, or murdered.

Benatar sums up this chapter arguing that considering that existence has no advantage over non-existence for the ones coming into existence, it is hard to see how the significant risk of a serious harm can be morally justified. If we take into account not only exceptionally severe harms that anyone can endure, but rather daily harms that are routine, then we’ll find that things are much worse even for the optimists. Thus according to him people who choose to reproduce are playing Russian Roulette with a loaded gun aimed, of course, not at their own heads, but at those of their future offspring.

Some Common Criticism

So as you can see from the arguments Benatar makes in the third chapter, in contrast to certain criticisms that his arguments are too “clinical” (especially regarding the asymmetry argument), Benatar’s motive is not to prevent every negative experience that anyone can experience. Benatar is not a mathematician or a statistician but an ethicist. He is bothered by the fact that existence is usually accompanied by a lot of suffering, not by a few negative experiences. It is this suffering that he seeks to prevent, and he argues that it comes without a cost for the unborn since the ones who don’t come into existence are not harmed by that in any way.

As aforesaid, many opponents claim that it doesn’t make sense to argue that it is better never to have been for the ones who never came into existence because how can something be better for the ones who never existed. To that Benatar replies that obviously it is not that by not coming into existence there is someone real who benefits from that. However, we can still say that it is better for someone that s/he didn’t come into existence, as long as we understand that this argument is a convenient form of expression for a much more complex idea. And this complex idea goes more or less as follows: if we compare two worlds – one in which someone exists and the other in which that someone doesn’t, one way to examine which world is better is by referring to the interests of the person who exists in one world (and only one world) out of the two possible worlds. Of course these interests exist only in one world and that is the one in which that person exists, but that doesn’t mean we can’t examine the value of the other possible world, and we can do that by referring to the interests of the person in the world in which s/he does exist. Therefore, we can argue about an existing person that for that person it is better never to have been. If someone doesn’t exist, we can argue that had s/he existed, it would have been better for that person had s/he never been. In any case we are arguing something about someone who does exist in one of the worlds.

It seems that the most common opposition to Benatar’s arguments is that as long as the positive outweighs the negative then life is worth living and if it is not then it is not. The explanations Benatar provides clarify that this argument is not only wrong but it doesn’t reflect people’s true perceptions because if they truly thought so they would be in favor of reproduction at any chance as long as they think that the one who comes into existence would experience more good than bad, they would think that we have a moral obligation to reproduce in cases we are sure the created people would have lives that constrain more good experiences than bad ones, they would regret that Mars is not populated if its population would have been mostly positive, and it would make sense to them to regret that someone never came into existence if that someone was expected to have a life that is supposedly more positive than negative.

If we’ll follow the logic of this opposition then it actually implies a mandatory examination, meaning, we need to reproduce and if we’ll find out that the created people are having more negative experiences than positive ones, then we were wrong to create them. And that obviously is a cruel implication. It is condemning some people to miserable lives only to retroactively figure out that we should have never created them. On the other hand, if we’ll avoid creating people in general, those who would have been miserable had we created them won’t suffer, and those who would have lived lives that are more good than bad wouldn’t miss or be deprived of anything, and won’t be harmed by anything. Therefore, even if we agree with this counter-argument to Benatar that claims that it is not true that it is always better never to have been but rather that it depends on whether the good parts outweigh the bad parts, still, the moral conclusion should be to never reproduce because we can never know in advance what would be the fate of the ones who will be created. So one doesn’t necessarily need to think like Benatar that even if the good outweighs the bad it is always better never to have been, but it is sufficient to realize that it is always a possibility that the bad would outweigh the good, and that this possibility is renewed with each case of reproduction because no one can ever know what kind of life that created person would have, to conclude that all cases of reproduction are morally wrong.

Even if not all cases of reproduction but only cases of reproduction of people who would live lives that are more bad than good are morally wrong, but each case of reproduction may create a life that is more bad than good, and no prevention of a creation of a new life harms the ones who will not be created, then clearly we should never create new people.

One doesn’t necessarily need to agree with Benatar that it is always better never to have been, it is sufficient to agree with his premise that no one is harmed by not being created to realize that we should be against reproduction in general because it opens the option not only of creating people that it would have been better for them never to have been because on the theoretical level existence has no advantage over non-existence, but also for people that in the most concrete level their specific existence is of a miserable and unworthy life.

Other critics argue that Benatar’s arguments are very unintuitive. To that he replies that generally speaking intuitions should be held very suspiciously since in many cases they are simply an expression of baseless biases. In the case of reproduction, he wonders why we would think that it is acceptable to cause someone so much suffering when avoiding it has no cost for that someone? In other words, how reliable is our intuition if it permits causing severe harms that could have easily been avoided with no cost to the harmed person? Such an intuition wouldn’t be respected in any other context. So why should we think that it deserves such respect only in cases of reproduction?

Facing critics in general, Benatar argues that even if his argument is false and it is not wrong to create new people, it is at least preferable. Although it is possible that potential people won’t regret being created if they are created, it is certain that they won’t regret not being created if they won’t be created. And since it is not in their interest to be created before they are created, a morally preferable course of action is to ensure they won’t be created.

Benatar suggests that the principle of caution is very appropriate here because no one is harmed by a false assumption regarding a preference not to be created (even if it is not true that someone would have preferred never to be created no one is harmed by not being created), but there would be someone who would be harmed by a false assumption regarding a preference to be created (if it is not true that someone would have preferred to be created there certainly is someone who is harmed by being created). In order to demonstrate this claim in a more concrete way, Benatar suggests imagining someone assuming that a fetus would develop to be a person who is glad to exist and therefore keep the pregnancy. If this assumption is wrong and the fetus would develop to be a person who is not glad to exist, we have created an unhappy if not a miserable person. But if someone makes the opposite assumption, meaning that the fetus would develop to be an unhappy person and therefore decide to stop the pregnancy, if that assumption was wrong and that fetus would have developed to be a person who is glad to exist, there wouldn’t be anyone who is harmed by this false assumption.

Probably due to his pioneering, organized thought, and the scarcity of alternatives, Benatar is disproportionately the thinker who is most associated with anti-natalism. For many, certainly in the academic world, anti-natalism and Benatar’s arguments are virtually the same. That’s why critics of anti-natalism mainly focus on Benatar’s arguments, and mostly his asymmetry argument. But there are many more anti-natalist arguments, and in fact, many anti-natalists disagree with the asymmetry argument. One of the strongest difficulties is as mentioned earlier, to accept the claim that preventing pain is good even if there is no one specific that benefits from this good. However, many are willing to accept this claim and they accept Benatar’s explanations that the meaning is not that it is good for someone who doesn’t exist that the pains that someone would experienced had that someone existed were prevented (as the ones who never have been don’t experience anything) but that it is good that someone didn’t experience pains that s/he would have experienced had s/he been created, but are struggling to understand why the same logic doesn’t apply to pleasures in non-existence. That’s to say, if preventing pain is good even if there is no one to benefit from this good because had that person existed experiencing pain would have been bad and therefore preventing this pain is good, it makes sense to them to claim that preventing pleasure should be accounted as ‘bad’ and not as ‘not bad’ as Benatar claims, since had that someone existed s/he would have enjoyed these pleasures and s/he is not harmed by not experiencing these pleasures only as long as that person stays in the status of ‘not existing’. But regarding pain Benatar doesn’t leave the harmed in non-existence knowing that by that he is attributing experiences to someone who has never been, but argues that it is good for that person because had s/he existed preventing pain would have been good for that person. By the same token, we can claim that had that person existed s/he would have enjoyed the good experiences and so preventing it from that person is bad. It can be labeled as ‘not bad’ only because under Benatar’s formulation the person always stays non-existing. The harmed on the other hand is who could have existed. In other words, it is totally valid to argue something about a situation in which someone could exist despite that s/he actually doesn’t, but what doesn’t make sense to these critics is that had that someone existed s/he would also experience pleasures, and therefore they fail to see the asymmetry.

Benatar replies that the source of error of this criticism is held with examining his argument as logical rather than axiological (relating to the study of values). Clearly, argues Benatar, from a logical standpoint we can argue that if pain is bad and therefore preventing it is good then if pleasure is good preventing it is bad, but from an axiological standpoint we don’t want to say that, and people don’t actually think so. Had people really thought that preventing pleasures is bad they couldn’t have supported the four asymmetries he suggested as support to his asymmetry argument and the asymmetry argument as the only reasonable explanation to these four very commonly accepted asymmetries. In other words, Benatar argues that the logical move of attributing negative value to preventing pleasures has a very significant and non-intuitive axiological price and that is that we should reject the supporting asymmetries as well. We couldn’t claim that while there is a moral obligation to prevent creating miserable people, there is no moral obligation to create happy people if preventing pleasures is bad, and there actually is a moral obligation to create happy people.

We couldn’t claim that while it is not strange to explain avoiding the creation of someone so as to prevent harming that person, it is strange to give as an explanation for the creation of someone that that person would benefit from that, since if preventing pleasures is bad, it is not only not strange to give that as explanation, people should actually have a moral incentive to create as many people as possible.

We couldn’t claim that while regretting the decision to create people could be for their sake, the decision not to create people couldn’t be for their sake, if preventing pleasures is bad. And we are supposed to regret our decision not to create someone because preventing pleasures is bad.

And we couldn’t claim that it makes sense to be sad about remote suffering, but that it doesn’t make sense to be sad about some unpopulated place, if preventing pleasure is bad. And we should be sorry for all the potential creatures that could have enjoyed their lives on Mars. If preventing pleasures is bad, we are supposed to be sorry for all the remote suffering but also about all the absence of pleasure of those that could have exist.

Most people don’t agree with any of these.

In any case, in order to avoid what some see as a problem with (3), or what others see as a problem in the relation between (3) and (4), we can look at Benatar’s asymmetry not in terms of what would be better for the ones who don’t yet exist, but rather from the aspect of moral duties of existing people regarding reproduction on the basis of the pain and pleasure asymmetry. Considering that there is no harm or risk in not creating people, and considering that there is no moral duty to create happy people but there is a moral duty not to create miserable people, clearly, it is better never to create new people, because to avoid the creation of a new person is not harming that person whether s/he would have been happy or miserable, and the creation of a person is not a moral duty in the case s/he would be happy but it is a moral duty to avoid it in case s/he would be miserable. Considering that we don’t know in advance whether the created person would be happy or miserable, we should avoid reproduction.

If people decide not to create a person, even if that person would have been happy had he been created, they didn’t violate or follow any moral duty. If people decide to create a person that turns out to be happy, they didn’t violate or follow any moral duty (if we ignore for argument’s sake the other anti-natalist arguments). If people decide not to create a person that is expected to be miserable they have followed a moral duty. And if they decide to create a person that is expected to be miserable they have violated a moral duty. Therefore, clearly in terms of moral duties, people should not reproduce because they have no way of telling whether the person they will create would be miserable and then they would violate a moral duty. On the other hand, if they will avoid creating a new person they may obey a moral duty, and they certainly won’t violate one.

And of course, we can determine whether reproduction is morally bad or good in completely different ways. Totally separate from Benatar’s arguments, we can and should consider reproduction as immoral for example because it is immoral to harm someone else without consent, because it is immoral to impose something on someone without that someone asking, wanting, needing that something, or without that something being in that someone’s interests, because it is immoral to put someone at risk of significant harms, because it is immoral to create someone since its creators want that but the created person has no will that it will happen before it does since no one has any will before being created, because it is immoral to create someone without any defined purpose and expecting that someone to find some purpose during life, because it is immoral to create someone in such an immoral, unfair, unjust, random and senseless world, because it is immoral to force a person to be someone that person didn’t choose but rather his genetic constitution, his utero environment, the behavior of his biological mother during the pregnancy, his living environment, his parents, his extended family, his culture, society etc. have designed, or because it is immoral to create someone who will necessarily harm many others only to sustain itself on a very basic level (and practically, the created person will probably harm countless others in various ways because this is the norm, because s/he would feel like it or whatever).

Namely, reproduction is immoral regardless of whether it would turn out retroactively to be preferable by the created person.

In any case, be it that you totally disagree or totally agree with Benatar’s basic arguments, it is hard to disagree with his tremendous contribution to raising awareness about this issue. The idea of resisting reproduction has a long history, but Benatar was the first to formulate the argument in a way that is organized, pronounced, coherent and independent of other factors.

Benatar’s argument, again, even if you find some flaws in it, is not incidental, it is not a footnote, and not an example for a different moral position, or a thought experiment, but a whole particular argument against reproduction, supported by rational moral justification. This is where its strength is, and this strength is recognized in the academic world as well, as many scholars philosophize with his argument since 2006 and to this day, within academic articles devoted to his ideas, within books about ethics, within academic conferences, online discussions etc. What Benatar has done to anti-natalism is similar to what Peter Singer has done to animal rights. He didn’t invent the issue and others have written things that are no less important and eye opening, but like Singer, he managed to formulate for people what they had been feeling before reading him, or has managed to make people understand what they have been feeling but couldn’t quite assemble it into a sharp and clear argument. There are many anti-natalists who agree with Benatar, and there are also many who don’t, but even they should see him as an exceptionally prominent groundbreaking thinker.